Book Reviews

Okay folks, buckle up because I'm about to get VERY controversial here. You thought the last book review about the Israel/ Palestinian conflict touched on some explosive issues? Well, that's nothing compared to this book review. Some sacred cows are about to be gored. So be prepared.

Madeleine L'Engle's "A Wrinkle in Time" is a terrible book.

Yeah, you heard me. "A Wrinkle in Time" is terrible. As a book "A Wrinkle in Time" has some of the worst characters and some of the most miserable and unrealistic dialogue that I have ever read. The plot is okay-ish and there are some trippy scenes (the image of rows of children on a street bouncing their balls and skipping rope in perfect time remains with me ever since I first read "A Wrinkle in Time" when I was in 6th grade) ... but in the end the characters are awful and the dialogue is horrible. And frankly, if the characters are awful and the dialogue is horrible then the book is beyond hope of redemption. I have never known a book to succeed in writing itself towards greatness or even competence when it is saddled with bad characters and bad dialogue. Period.

So why is "A Wrinkle in Time"- widely considered a classic piece of children's fiction- such a bad book? Well, before I get into that in depth let me just give my own personal history of "A Wrinkle in Time." As I mentioned before I read "A Wrinkle in Time" in middle school. Indeed "A Wrinkle in Time" is not a self-contained book but the first part of a quadrilogy. There are four books, all of which I read in middle school. The first book involves Meg and her creepy-ass little brother and an unmemorable teen boy love interest traveling across space to rescue Meg's dad. The next two books are also not very memorable (one involved Meg traveling inside her creepy-ass little brother's mitochondria or something). The last book, "Many Waters," I remember reading and actually enjoying a little bit probably because Meg and her creepy-ass little brother weren't in that book at all. Instead Meg's older twin brothers time travel back to before the Great Flood where they meet Noah (of "He built the Ark" fame) and Noah's family. It was kind of interesting and ethically complicated too because the older twin brothers knew that Noah had to build an Ark before the Great Flood came but that Noah couldn't fit all the human civilization in his boat.... so a lot of good people were about to die. That was a lot more interesting to me than Meg and the creepy-ass little brother battling Nameless Cloud of Evil in "A Wrinkle in Time." Plus Noah and his family were about waist-high to modern humans and all the women were topless for some reason. I remember that.

Anyway, in the "A Wrinkle in Time" series the first book seemed to be the worst to my 12-year-old brain. Back in those days I tended to blame myself if I found a book to be difficult to like, especially a book with a respected legacy like "A Wrinkle in Time." Clearly I was too dumb to understand it or appreciate it. Now that I'm almost forty I've managed to accrue enough self-esteem to realize that no.... no.... 12-year-old me was right. "A Wrinkle in Time" really is a bad book.

So let's review the plot of "A Wrinkle in Time." It starts off strongly enough. Meg Murry, age fourteen, is being kept awake by a ferocious thunderstorm in the middle of the night. She creeps into the kitchen for a snack, where she meets her little brother Charles and their mother. The family settles down for a cozy little midnight snack of liverwurst and cream cheese sandwiches and hot cocoa. So far so good. In fact, this intimate and sweet scene is probably the best in the book. When Meg says that she hates liverwurst and wants a tomato and cream cheese sandwich instead, Charles pulls out their last remaining tomato from the refrigerator. "All right if I use it on Meg, Mother?" Charles asks. "To what better use could it be put?" their mother replies. It's a beautiful exchange. Two sentences, awkwardly spoken (like all the dialogue in "A Wrinkle in Time") but nevertheless indicating that Meg's family is loving if a bit intellectual. Meg has a safe space to go to despite all her troubles at school and fighting with teens.

Anyway, don't let the beginning scene fill you with hope about the rest of the book because the story goes downhill fast. The Murry family's midnight snack is interrupted by a dotty old woman named Mrs. Whatsit. L'Engle obviously wanted to portray Mrs. Whatsit as an adorably eccentric woman but instead Mrs. Whatsit comes of as an insane old bag lady who's about as funny as Jar Jar Binks. Mrs. Whatsit makes Meg take off her wet boots and socks, stinking up the kitchen as everyone is trying to eat. Then Mrs. Whatsit demands sandwiches, falls off her chair (ho ho, how funny!), and lays on the floor, refusing to get up. "Have YOU ever tried getting up with a sprained dignity?" Sigh. At this point the Murry family should call the police and have Mrs. Whatsit bundled off their property. They don't though.

The book goes on. Mrs. Whatsit leaves. The Murry family makes breakfast before school the next day and the reader starts to get her first taste of the awfulness of the dialogue that marks the rest of "A Wrinkle in Time." Meg's older teen brothers scold her over the breakfast table and oh boy is the conversation badly-written! Not only is the dialogue unnatural and stiff and unlike anything a human being would say let alone a teenage boy.... it also seems to be about 60% mansplaining. As I reread "A Wrinkle in Time" I couldn't help but be amazed at how many of the scenes seem to involve some male figure mansplaining or acting in a condescending manner towards Meg. Her older teenage brothers mansplain to her and her mother. "You have a great mind and all, Mother, but you don't have much SENSE. And certainly Meg and Charles don't ... Don't take everything so PERSONALLY, Meg! Use a happy medium for once!" says Sandy, Meg's sixteen-year-old brother. And frankly if a sixteen-year-old boy has ever used the term "happy medium" naturally in a sentence then flying centaurs really do exist. Meg's creepy little 5-year-old brother Charles also mansplains to her ("You have to be patient, Meg") but some of the most problematic mansplaining comes from Meg's fourteen-year-old love interest Calvin. "Come on, Meg. You know it isn't true, I know it isn't true," Calvin says in one scene after Meg becomes understandably upset over the implication that Meg's dad may have disappeared because he fell in love with another woman. "And how anybody after one look at your mother could believe any man would leave her for another woman just shows how far jealousy will make people go."

Wow. So many problematic ideas in that statement. Yes. It is impossible for a man to leave a woman if the woman is beautiful. Beautiful women never have unfaithful husbands. Oh, and dear reader, please read the sentence "And how anybody after one look at your mother could believe any man could leave her for another woman just shows how far jealousy will make people go," and imagine those words coming out of the mouth of a fourteen-year-old boy. If you find that you can't imagine that at all, congratulations. You know how actual people talk.

Scene after scene in "A Wrinkle in Time" is filled with this horrible, unrealistic dialogue. I don't know when I started to realize that "A Wrinkle in Time" was just a flat-out terrible book. Maybe it was when Meg randomly made what was supposed to be a joke but comes out as weird word salad. "Mother, Charles says I'm not one thing or the other, not flesh nor fowl nor good red herring." (Meg, seriously..... what the fuck?) Or maybe when Meg and her mother have a conversation but they sound less like a mother and daughter and more like some 26th century robot actors trying to interpret ancient 20th century flesh-people plays for modern robot audiences. "I'm blessed with more brains and opportunities than many people," Meg's mom says casually to Meg, "But there's nothing about me that breaks out of the ordinary mold." Bravo Madeleine L'Engle! What amazing dialogue! *air kiss.* I have never read such natural conversation since that infamous bad Japanese video game translation: "All your base are belong to us."

The plot of "A Wrinkle in Time" is only marginally better than the dialogue. Meg, Charles and Calvin travel across space with the help of three witches so they can rescue Meg and Charles' dad. Oh, and they have to battle a Nameless Cloud of Evil. The Nameless Cloud of Evil doesn't really have a motive. It's just an Evil Cloud that consumes planets and turns civilizations into Orwellian dictatorships. Meg and Calvin rescue Meg's father from one of these planets but they have to leave Charles behind and Meg almost dies when they time-warp (or "wrinkle") off the planet. In another hair-tearingly awful example of Madeleine L'Engle's stiff, unnatural dialogue, we get a scene where Meg lies on the grass close to death. Meg's dad hasn't seen her since she was a little girl and Meg's dad also has been imprisoned in a hellish suspension for half a decade. Instead of weeping over his daughter or laughing in relief over his release from prison or screaming in horror over the fact that his youngest son is still imprisoned across space ... Meg's dad decides to chat about physics with Calvin. "Time is different on Camazotz, anyhow. Our time, inadequate though it is, at least is straightforward. It may not be even fully one-dimensional, because it can't move back and forth on its line, only ahead- but at least it's consistent in its direction." Yeah, sure, fine man. So are you going to start CPR on Meg? Or...?

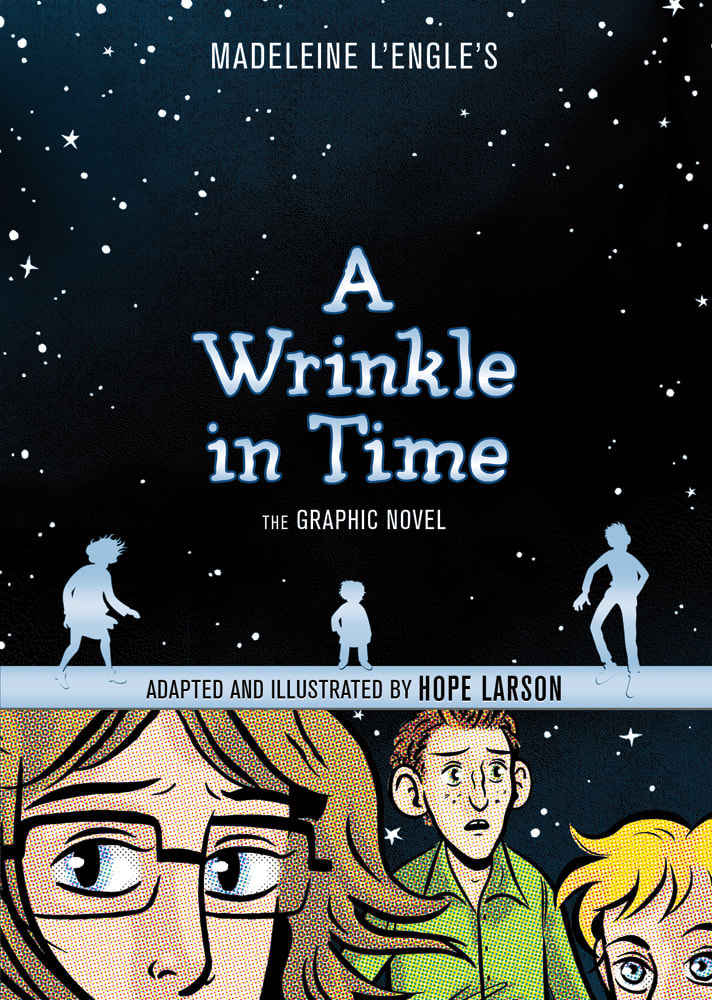

Hope Larson adapted Madeleine L'Engle's "A Wrinkle in Time" to graphic novel format in 2012. L'Engle originally wrote the book in 1962. Larson's illustrations are competent but not very memorable. Larson frankly sacrifices too much of her own talent in order to remain slavishly faithful to Madeleine L'Engle's original text. The adaptation is bulky, retaining too many scenes that really should have been cut. "A Wrinkle in Time: The Graphic Novel" would have really benefited with a more ruthless editor. I would have loved an abridged version of "A Wrinkle in Time" with maybe an adapter who was unafraid to re-write some dialogue. A lot of the problems with Larson's "A Wrinkle in Time" adaptation have to do with the source material, however, so the graphic novel already started out with two strikes against it.

Because, as I have said before, "A Wrinkle in Time" is a really bad book.

Madeleine L'Engle's "A Wrinkle in Time" is a terrible book.

Yeah, you heard me. "A Wrinkle in Time" is terrible. As a book "A Wrinkle in Time" has some of the worst characters and some of the most miserable and unrealistic dialogue that I have ever read. The plot is okay-ish and there are some trippy scenes (the image of rows of children on a street bouncing their balls and skipping rope in perfect time remains with me ever since I first read "A Wrinkle in Time" when I was in 6th grade) ... but in the end the characters are awful and the dialogue is horrible. And frankly, if the characters are awful and the dialogue is horrible then the book is beyond hope of redemption. I have never known a book to succeed in writing itself towards greatness or even competence when it is saddled with bad characters and bad dialogue. Period.

So why is "A Wrinkle in Time"- widely considered a classic piece of children's fiction- such a bad book? Well, before I get into that in depth let me just give my own personal history of "A Wrinkle in Time." As I mentioned before I read "A Wrinkle in Time" in middle school. Indeed "A Wrinkle in Time" is not a self-contained book but the first part of a quadrilogy. There are four books, all of which I read in middle school. The first book involves Meg and her creepy-ass little brother and an unmemorable teen boy love interest traveling across space to rescue Meg's dad. The next two books are also not very memorable (one involved Meg traveling inside her creepy-ass little brother's mitochondria or something). The last book, "Many Waters," I remember reading and actually enjoying a little bit probably because Meg and her creepy-ass little brother weren't in that book at all. Instead Meg's older twin brothers time travel back to before the Great Flood where they meet Noah (of "He built the Ark" fame) and Noah's family. It was kind of interesting and ethically complicated too because the older twin brothers knew that Noah had to build an Ark before the Great Flood came but that Noah couldn't fit all the human civilization in his boat.... so a lot of good people were about to die. That was a lot more interesting to me than Meg and the creepy-ass little brother battling Nameless Cloud of Evil in "A Wrinkle in Time." Plus Noah and his family were about waist-high to modern humans and all the women were topless for some reason. I remember that.

Anyway, in the "A Wrinkle in Time" series the first book seemed to be the worst to my 12-year-old brain. Back in those days I tended to blame myself if I found a book to be difficult to like, especially a book with a respected legacy like "A Wrinkle in Time." Clearly I was too dumb to understand it or appreciate it. Now that I'm almost forty I've managed to accrue enough self-esteem to realize that no.... no.... 12-year-old me was right. "A Wrinkle in Time" really is a bad book.

So let's review the plot of "A Wrinkle in Time." It starts off strongly enough. Meg Murry, age fourteen, is being kept awake by a ferocious thunderstorm in the middle of the night. She creeps into the kitchen for a snack, where she meets her little brother Charles and their mother. The family settles down for a cozy little midnight snack of liverwurst and cream cheese sandwiches and hot cocoa. So far so good. In fact, this intimate and sweet scene is probably the best in the book. When Meg says that she hates liverwurst and wants a tomato and cream cheese sandwich instead, Charles pulls out their last remaining tomato from the refrigerator. "All right if I use it on Meg, Mother?" Charles asks. "To what better use could it be put?" their mother replies. It's a beautiful exchange. Two sentences, awkwardly spoken (like all the dialogue in "A Wrinkle in Time") but nevertheless indicating that Meg's family is loving if a bit intellectual. Meg has a safe space to go to despite all her troubles at school and fighting with teens.

Anyway, don't let the beginning scene fill you with hope about the rest of the book because the story goes downhill fast. The Murry family's midnight snack is interrupted by a dotty old woman named Mrs. Whatsit. L'Engle obviously wanted to portray Mrs. Whatsit as an adorably eccentric woman but instead Mrs. Whatsit comes of as an insane old bag lady who's about as funny as Jar Jar Binks. Mrs. Whatsit makes Meg take off her wet boots and socks, stinking up the kitchen as everyone is trying to eat. Then Mrs. Whatsit demands sandwiches, falls off her chair (ho ho, how funny!), and lays on the floor, refusing to get up. "Have YOU ever tried getting up with a sprained dignity?" Sigh. At this point the Murry family should call the police and have Mrs. Whatsit bundled off their property. They don't though.

The book goes on. Mrs. Whatsit leaves. The Murry family makes breakfast before school the next day and the reader starts to get her first taste of the awfulness of the dialogue that marks the rest of "A Wrinkle in Time." Meg's older teen brothers scold her over the breakfast table and oh boy is the conversation badly-written! Not only is the dialogue unnatural and stiff and unlike anything a human being would say let alone a teenage boy.... it also seems to be about 60% mansplaining. As I reread "A Wrinkle in Time" I couldn't help but be amazed at how many of the scenes seem to involve some male figure mansplaining or acting in a condescending manner towards Meg. Her older teenage brothers mansplain to her and her mother. "You have a great mind and all, Mother, but you don't have much SENSE. And certainly Meg and Charles don't ... Don't take everything so PERSONALLY, Meg! Use a happy medium for once!" says Sandy, Meg's sixteen-year-old brother. And frankly if a sixteen-year-old boy has ever used the term "happy medium" naturally in a sentence then flying centaurs really do exist. Meg's creepy little 5-year-old brother Charles also mansplains to her ("You have to be patient, Meg") but some of the most problematic mansplaining comes from Meg's fourteen-year-old love interest Calvin. "Come on, Meg. You know it isn't true, I know it isn't true," Calvin says in one scene after Meg becomes understandably upset over the implication that Meg's dad may have disappeared because he fell in love with another woman. "And how anybody after one look at your mother could believe any man would leave her for another woman just shows how far jealousy will make people go."

Wow. So many problematic ideas in that statement. Yes. It is impossible for a man to leave a woman if the woman is beautiful. Beautiful women never have unfaithful husbands. Oh, and dear reader, please read the sentence "And how anybody after one look at your mother could believe any man could leave her for another woman just shows how far jealousy will make people go," and imagine those words coming out of the mouth of a fourteen-year-old boy. If you find that you can't imagine that at all, congratulations. You know how actual people talk.

Scene after scene in "A Wrinkle in Time" is filled with this horrible, unrealistic dialogue. I don't know when I started to realize that "A Wrinkle in Time" was just a flat-out terrible book. Maybe it was when Meg randomly made what was supposed to be a joke but comes out as weird word salad. "Mother, Charles says I'm not one thing or the other, not flesh nor fowl nor good red herring." (Meg, seriously..... what the fuck?) Or maybe when Meg and her mother have a conversation but they sound less like a mother and daughter and more like some 26th century robot actors trying to interpret ancient 20th century flesh-people plays for modern robot audiences. "I'm blessed with more brains and opportunities than many people," Meg's mom says casually to Meg, "But there's nothing about me that breaks out of the ordinary mold." Bravo Madeleine L'Engle! What amazing dialogue! *air kiss.* I have never read such natural conversation since that infamous bad Japanese video game translation: "All your base are belong to us."

The plot of "A Wrinkle in Time" is only marginally better than the dialogue. Meg, Charles and Calvin travel across space with the help of three witches so they can rescue Meg and Charles' dad. Oh, and they have to battle a Nameless Cloud of Evil. The Nameless Cloud of Evil doesn't really have a motive. It's just an Evil Cloud that consumes planets and turns civilizations into Orwellian dictatorships. Meg and Calvin rescue Meg's father from one of these planets but they have to leave Charles behind and Meg almost dies when they time-warp (or "wrinkle") off the planet. In another hair-tearingly awful example of Madeleine L'Engle's stiff, unnatural dialogue, we get a scene where Meg lies on the grass close to death. Meg's dad hasn't seen her since she was a little girl and Meg's dad also has been imprisoned in a hellish suspension for half a decade. Instead of weeping over his daughter or laughing in relief over his release from prison or screaming in horror over the fact that his youngest son is still imprisoned across space ... Meg's dad decides to chat about physics with Calvin. "Time is different on Camazotz, anyhow. Our time, inadequate though it is, at least is straightforward. It may not be even fully one-dimensional, because it can't move back and forth on its line, only ahead- but at least it's consistent in its direction." Yeah, sure, fine man. So are you going to start CPR on Meg? Or...?

Hope Larson adapted Madeleine L'Engle's "A Wrinkle in Time" to graphic novel format in 2012. L'Engle originally wrote the book in 1962. Larson's illustrations are competent but not very memorable. Larson frankly sacrifices too much of her own talent in order to remain slavishly faithful to Madeleine L'Engle's original text. The adaptation is bulky, retaining too many scenes that really should have been cut. "A Wrinkle in Time: The Graphic Novel" would have really benefited with a more ruthless editor. I would have loved an abridged version of "A Wrinkle in Time" with maybe an adapter who was unafraid to re-write some dialogue. A lot of the problems with Larson's "A Wrinkle in Time" adaptation have to do with the source material, however, so the graphic novel already started out with two strikes against it.

Because, as I have said before, "A Wrinkle in Time" is a really bad book.

After each Passover Seder my family would always enthusiastically exclaim "Next year in Jerusalem!" before finally- FINALLY!- getting down to the enjoyable task of eating dinner. We would say this phrase happily not because we actually wished to go to Jerusalem but because we were relieved that the hours-long seder was over. "Next year in Jerusalem!" was the ending bell. It was the phrase marking the end of an evening full of dull prayer and queasy justifications for God killing a bunch of Egyptian babies. We never really thought about what the phrase literally meant. Nobody at our seders in reality wanted to go to Jerusalem. And if any of us felt a little guilty about our lack of yearning for Israel, a quick read from Guy DeLisle's excellent comic memoir"Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City" would have quickly squelched it. In "Jerusalem" DeLisle demurely and amusingly portrays his year in Israel with his wife and two small children. DeLisle's Jerusalem is a city of hellish heat, awful traffic jams, frustrating bureaucracy, intimidating military presence, and seething anger occasionally boiling over into all-out war. Next year in Jerusalem? No thank you. I'm good.

Guy DeLisle is a French-Canadian cartoonist and self-described atheist with Catholic roots. His wife Nadine DeLisle is of similar background and she works as an administrator for the famous international medical aid group "Medicins Sans Frontieres" ("Doctors Without Borders" for us 'Mericans). When Nadine is transferred to Jerusalem for a year to assist MSF in the poverty-stricken Palestinian areas. Guy DeLisle and their two young children accompany her. The book opens with Guy DeLisle trying to calm his fussy two-year-old daughter on the 20 hour flight from Montreal to Tel Aviv. A stout elderly Russian passenger sitting next to DeLisle offers to calm the toddler despite speaking no English or French (the only two languages DeLisle speaks). The old man and the toddler play happily for hours. DeLisle notices, while watching the two play, that the old Russian has numbers tattooed on the inside of his right forearm. "Good God! This guy is a camp survivor." The rest of "Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City" is not at all a flattering picture of Israel so it is interesting that DeLisle chose to open his book with this reminder that Jews are very much the oppressed as well as the oppressors.

One in Jerusalem, the DeLisles settle in. Compared to some of Guy DeLisle's past abodes (Pyongyang springs to mind) Jerusalem is not too bad. It is nevertheless a grim place, full of cement apartment buildings, construction, armed military police, traffic, heat, daycares that close at only 1pm (boy did that part trigger me!) and grim little grocery stores that sell no beer, pork, or wine and are closed Friday through Saturday. DeLisle is tempted to shop at a nearby modern supermarket that sells all the forbidden foreign foods and is open all week. His wife's work colleagues forbid it. The supermarket is located in an area full of far-right Jewish settlers known for attacking and displacing impoverished Palestinian villagers. Supporting settler-owned businesses is a no-no. DeLisle refrains, regretfully. He can't help but notice ruefully, however, that plenty of Palestinian women shop at the same shiny supermarket. DeLisle enviously watches the women in their hijabs walking back to the bus stop with their bags full of Creamed Wheat and Campbells Chicken Noodle soup.

The constant clashes between Israel and the Palestinians are considered the Platonic ideal of "it's complicated." When it comes to the issue of Israeli settlements v. Palestinians Guy DeLisle is obviously biased since he receives most of his information from his wife and her MSF doctor colleagues who see the suffering of the Palestinians up close. DeLisle, however, wisely keeps his own views of the conflict confined to his physical observations. DeLisle draws the thuggish Israeli soldiers and settlers who tote massive automatic rifles on their shoulders everywhere they go, whether to the zoo or to a cafe. DeLisle draws his Palestinian art students at a women's college in Abu Dis. The women are all veiled, all thin, and shockingly under-educated about art even when they are majoring in artistic studies and drawing. DeLisle draws the ultra-orthodox Jewish neighborhood of Mea Shearim where "Families average seven kids, and considering how exhausted I am with two, I can only imagine how the women must feel." (This observation of DeLisle's is accompanied by a quick sketch of an ultra-orthodox Jewish woman, pale and exhausted beneath her wig, surrounded by five children and noticeably pregnant with her sixth.) DeLisle draws the baseball-sized rocks that Palestinians hurl at Israeli soldiers, only to be met with tear gas in response. DeLisle draws the nets that stretch between opposing buildings in the city of Hebron. "(The nets were) put up to protect passersby from objects thrown at them by settlers living in adjacent houses. Now, they toss down all kinds of trash that hangs there disgracefully."

One aspect of Israel that comes as a surprise to DeLisle is how divided Israeli Jews are when it comes to politics in their country. The rest of the world sees Israeli Jews as a monolithic block fighting against the Palestinians. The truth is the exact opposite. The far-right Israeli settlers torment Palestinian villagers populations by expanding illegal settlements into Palestinian cities. The moderate Jewish population of Israel are appalled at the actions of settlers and criticize the right-wing Israeli government for turning a blind eye towards the abuses perpetrated by Israeli settlers towards Palestinians. A group of ex-Israeli soldiers founded a group called "Breaking the Silence" where they recount how the Israeli government forced them to block off Palestinian streets, board up Palestinian businesses and evict Palestinians from their own homes for no reason except to allow Israeli settlers to move in and take over. Horrified that they were being forced to do this, the Israeli soldiers give tours of settlements to foreign tourists, describing the oppression visited upon Palestinians by the Israeli settlers. According to the founders of "Breaking the Silence," far-right Israeli settlements are backed quietly (and illegally) by the right-wing Israeli government. The moderate Israeli media is likewise sympathetic towards the suffering of Palestinians at the hands of far-right Israeli settlers. Plus there are divisions between the ultra-orthodox and reform Jewish community in Israel. The Talmud forbids the ultra-orthodox men from working so ultra-orthodox communities live off the taxpayer money generated by working reform Jewish populations. It is understandable that reform Jews are resentful towards the ultra-orthodox populations. In one scene in "Jerusalem" DeLisle travels with a tour group of mostly women in the ultra-orthodox neighborhood of Mea Shearim. DeLisle notices one ultra-orthodox man yelling in Hebrew while tying his shoe. DeLisle doesn't understand Hebrew and assumes the man is just talking on a bluetooth. "He talks out loud, his eyes fixed on his shoes. In fact, he's talking to our group, asking us to leave the quarter. But since he can't be seen speaking with women, he's using this indirect approach.

It's not surprising that the Jewish population of Israel is so divided among itself. We Jews are a very argumentative sort. It's rather like the joke my grandmother recounted in a book she wrote. It goes, and I paraphrase, "There was a Jew who was stranded on a desert island. Fortunately he had a lot of resources so he built himself a farm and a house and a garden and a synagogue and a second synagogue. When rescuers came to the desert island, they admired all that he had built but they were curious. 'Why did you build two synagogues? You're the only person on this island.' The Jew replied, 'Oh, that's the synagogue that I DON'T go to.'"

DeLisle's own self-portrait seems to indicate his wish to at least appear unbiased. DeLisle draws himself rather adorably as a benignant, clueless, almost "Hello Kitty" type of observer. The cartoon face of DeLisle consists of two rather surprised, clueless and good-natured black dots for eyes and a stylized, pie-slice nose. One panel DeLisle drew struck me as particularly cute and perhaps the epitome of what it means to be an expatriate used to surviving long periods in the harshest corners of he world. When DeLisle wakes up one morning to find his driver's side car window smashed and the radio stolen, he has no choice but to drive the window-less car to a repair shop and get the window replaced. The portrait of DeLisle driving with his coat buttoned past his nose to protect his face from the highway-speed gusts of wind and sand blowing in through his broken window struck me as oddly hilarious. Just another clueless yet good-natured white expatriate adapting to whatever challenges a foreign land throws at him.

After a year Nadine's shift with MSF in Jerusalem ends and the DeLisles get out of Israel just in time. The Israeli government, perhaps annoyed that MSF helps Palestinian populations, targets the houses of MSF administrators with "demolition notices." The DeLisle's house is given a demolition notice. "They say it was illegally built." Some MSF administrators doubt this, believing that the demolition notices are an intimidation tactic by the Israeli government to keep MSF out of Palestinian territories. As the DeLisles head to the airport at Tel Aviv on their way back to Canada, Guy DeLisle stops by a house where a Palestinian family has just been evicted and a Jewish settler family is moving in. DeLisle sees a large bearded man in a yarmulke standing on the roof of the house. As the bearded man watches the DeLisle family leave to board the cab to the airport, he smiles. "It's my house now!" the bearded man yells. It's a depressing full circle. The oppressed have become the oppressors. It is why, in my opinion, the truly Jewish among us say "Next year in Jerusalem." Always next year. Always the next time. Not now. Let it remain a dream. If we go now, we will see it for the cruel reality it is.

Guy DeLisle is a French-Canadian cartoonist and self-described atheist with Catholic roots. His wife Nadine DeLisle is of similar background and she works as an administrator for the famous international medical aid group "Medicins Sans Frontieres" ("Doctors Without Borders" for us 'Mericans). When Nadine is transferred to Jerusalem for a year to assist MSF in the poverty-stricken Palestinian areas. Guy DeLisle and their two young children accompany her. The book opens with Guy DeLisle trying to calm his fussy two-year-old daughter on the 20 hour flight from Montreal to Tel Aviv. A stout elderly Russian passenger sitting next to DeLisle offers to calm the toddler despite speaking no English or French (the only two languages DeLisle speaks). The old man and the toddler play happily for hours. DeLisle notices, while watching the two play, that the old Russian has numbers tattooed on the inside of his right forearm. "Good God! This guy is a camp survivor." The rest of "Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City" is not at all a flattering picture of Israel so it is interesting that DeLisle chose to open his book with this reminder that Jews are very much the oppressed as well as the oppressors.

One in Jerusalem, the DeLisles settle in. Compared to some of Guy DeLisle's past abodes (Pyongyang springs to mind) Jerusalem is not too bad. It is nevertheless a grim place, full of cement apartment buildings, construction, armed military police, traffic, heat, daycares that close at only 1pm (boy did that part trigger me!) and grim little grocery stores that sell no beer, pork, or wine and are closed Friday through Saturday. DeLisle is tempted to shop at a nearby modern supermarket that sells all the forbidden foreign foods and is open all week. His wife's work colleagues forbid it. The supermarket is located in an area full of far-right Jewish settlers known for attacking and displacing impoverished Palestinian villagers. Supporting settler-owned businesses is a no-no. DeLisle refrains, regretfully. He can't help but notice ruefully, however, that plenty of Palestinian women shop at the same shiny supermarket. DeLisle enviously watches the women in their hijabs walking back to the bus stop with their bags full of Creamed Wheat and Campbells Chicken Noodle soup.

The constant clashes between Israel and the Palestinians are considered the Platonic ideal of "it's complicated." When it comes to the issue of Israeli settlements v. Palestinians Guy DeLisle is obviously biased since he receives most of his information from his wife and her MSF doctor colleagues who see the suffering of the Palestinians up close. DeLisle, however, wisely keeps his own views of the conflict confined to his physical observations. DeLisle draws the thuggish Israeli soldiers and settlers who tote massive automatic rifles on their shoulders everywhere they go, whether to the zoo or to a cafe. DeLisle draws his Palestinian art students at a women's college in Abu Dis. The women are all veiled, all thin, and shockingly under-educated about art even when they are majoring in artistic studies and drawing. DeLisle draws the ultra-orthodox Jewish neighborhood of Mea Shearim where "Families average seven kids, and considering how exhausted I am with two, I can only imagine how the women must feel." (This observation of DeLisle's is accompanied by a quick sketch of an ultra-orthodox Jewish woman, pale and exhausted beneath her wig, surrounded by five children and noticeably pregnant with her sixth.) DeLisle draws the baseball-sized rocks that Palestinians hurl at Israeli soldiers, only to be met with tear gas in response. DeLisle draws the nets that stretch between opposing buildings in the city of Hebron. "(The nets were) put up to protect passersby from objects thrown at them by settlers living in adjacent houses. Now, they toss down all kinds of trash that hangs there disgracefully."

One aspect of Israel that comes as a surprise to DeLisle is how divided Israeli Jews are when it comes to politics in their country. The rest of the world sees Israeli Jews as a monolithic block fighting against the Palestinians. The truth is the exact opposite. The far-right Israeli settlers torment Palestinian villagers populations by expanding illegal settlements into Palestinian cities. The moderate Jewish population of Israel are appalled at the actions of settlers and criticize the right-wing Israeli government for turning a blind eye towards the abuses perpetrated by Israeli settlers towards Palestinians. A group of ex-Israeli soldiers founded a group called "Breaking the Silence" where they recount how the Israeli government forced them to block off Palestinian streets, board up Palestinian businesses and evict Palestinians from their own homes for no reason except to allow Israeli settlers to move in and take over. Horrified that they were being forced to do this, the Israeli soldiers give tours of settlements to foreign tourists, describing the oppression visited upon Palestinians by the Israeli settlers. According to the founders of "Breaking the Silence," far-right Israeli settlements are backed quietly (and illegally) by the right-wing Israeli government. The moderate Israeli media is likewise sympathetic towards the suffering of Palestinians at the hands of far-right Israeli settlers. Plus there are divisions between the ultra-orthodox and reform Jewish community in Israel. The Talmud forbids the ultra-orthodox men from working so ultra-orthodox communities live off the taxpayer money generated by working reform Jewish populations. It is understandable that reform Jews are resentful towards the ultra-orthodox populations. In one scene in "Jerusalem" DeLisle travels with a tour group of mostly women in the ultra-orthodox neighborhood of Mea Shearim. DeLisle notices one ultra-orthodox man yelling in Hebrew while tying his shoe. DeLisle doesn't understand Hebrew and assumes the man is just talking on a bluetooth. "He talks out loud, his eyes fixed on his shoes. In fact, he's talking to our group, asking us to leave the quarter. But since he can't be seen speaking with women, he's using this indirect approach.

It's not surprising that the Jewish population of Israel is so divided among itself. We Jews are a very argumentative sort. It's rather like the joke my grandmother recounted in a book she wrote. It goes, and I paraphrase, "There was a Jew who was stranded on a desert island. Fortunately he had a lot of resources so he built himself a farm and a house and a garden and a synagogue and a second synagogue. When rescuers came to the desert island, they admired all that he had built but they were curious. 'Why did you build two synagogues? You're the only person on this island.' The Jew replied, 'Oh, that's the synagogue that I DON'T go to.'"

DeLisle's own self-portrait seems to indicate his wish to at least appear unbiased. DeLisle draws himself rather adorably as a benignant, clueless, almost "Hello Kitty" type of observer. The cartoon face of DeLisle consists of two rather surprised, clueless and good-natured black dots for eyes and a stylized, pie-slice nose. One panel DeLisle drew struck me as particularly cute and perhaps the epitome of what it means to be an expatriate used to surviving long periods in the harshest corners of he world. When DeLisle wakes up one morning to find his driver's side car window smashed and the radio stolen, he has no choice but to drive the window-less car to a repair shop and get the window replaced. The portrait of DeLisle driving with his coat buttoned past his nose to protect his face from the highway-speed gusts of wind and sand blowing in through his broken window struck me as oddly hilarious. Just another clueless yet good-natured white expatriate adapting to whatever challenges a foreign land throws at him.

After a year Nadine's shift with MSF in Jerusalem ends and the DeLisles get out of Israel just in time. The Israeli government, perhaps annoyed that MSF helps Palestinian populations, targets the houses of MSF administrators with "demolition notices." The DeLisle's house is given a demolition notice. "They say it was illegally built." Some MSF administrators doubt this, believing that the demolition notices are an intimidation tactic by the Israeli government to keep MSF out of Palestinian territories. As the DeLisles head to the airport at Tel Aviv on their way back to Canada, Guy DeLisle stops by a house where a Palestinian family has just been evicted and a Jewish settler family is moving in. DeLisle sees a large bearded man in a yarmulke standing on the roof of the house. As the bearded man watches the DeLisle family leave to board the cab to the airport, he smiles. "It's my house now!" the bearded man yells. It's a depressing full circle. The oppressed have become the oppressors. It is why, in my opinion, the truly Jewish among us say "Next year in Jerusalem." Always next year. Always the next time. Not now. Let it remain a dream. If we go now, we will see it for the cruel reality it is.

Graphic novels and novelizations epitomize the phrase "A picture is worth a thousand words." Straight-up novels can only convey so much through mere words. Graphic novels, especially well-drawn graphic novels like the graphic novelization of Neil Gaiman's "American Gods," convey a massive amount of information in terms of detail and setting and emotion that simple words on a page can't show. Neil Gaiman's words are literally the same in the graphic novel as they are in his book, but like Shakespeare's words gaining new meaning when his plays are placed in different settings by innovative directors, Gaiman's dialogue and characters take on new meanings in the graphic novelization of "American Gods" that they definitely did not have in the book. Gaiman is aided by the extraordinary illustrators P. Craig Russell, Scott Hampton, Walter Simonson, Colleen Doran (expertly imitating 19th century illustrator Kate Greenaway's work in her graphic novel interpretation of Gaiman's short story about a female convict from Cornwall who is banished to the American colonies) and Glenn Fabry (whose masterfully-drawn and -ahem- straightforward illustration of a bashful plump Omani souvenir merchant who hooks up with a sexy djinn made me have to tilt the book a bit while reading at Starbucks).

In "American Gods" a man named Shadow, a guy who just served his time in prison for robbery, is offered a job by a "Mr. Wednesday" as a bodyguard. Shadow is at loose ends. He's an ex-criminal, his wife died while he was in prison and he has no job and nowhere to go. He is almost given no choice but to accept Mr. Wednesday's job. Mr. Wednesday turns out to be the personification of the Norse God Odin who, along with other pre-Christian Indo-European gods and various mystical figures masquerading as immigrants, is planning a war against various new gods such as the god of the internet and the god of television.

In the original novel "American Gods" Neil Gaiman is rather vague in describing Shadow physically. Shadow is a large, burly guy. "He was big enough and looked don't-fuck-with-me enough(.)" Gaiman implies in the book that Shadow is rather swarthy, leading a white prison guard at the beginning of the novel to ask him "And what are you? A spic? A gypsy? Maybe you got n***** blood in you. You got n***** blood in you, Shadow?" This exchange does not translate well in the graphic novel since Shadow is drawn as unambiguously black.

Shadow's blackness in the graphic novel of "American Gods" adds dimensions to the story that are missing in the book. The scene where Mr. Wednesday an old white man, intimidates Shadow into being his bodyguard takes on an uncomfortable sheen. The fact that Mr. Wednesday turns out to be a Scandinavian god, a figure in a pre-Christian culture that is fetishized by white supremacists, only makes the situation more uncomfortable. When Mad Sweeney, a leprechaun who takes on the form of a 7-foot white trucker with a baseball hat, punches Shadow in a bar it's hard not to see a MAGA-era hate crime. Mad Sweeney's baseball hat reads "The only woman I ever loved was another man's wife.... my mother." Still, it looks a lot like a MAGA hat. When another old white god, Czernobog, talks to Shadow about "your master" Mr. Wednesday the phrase suddenly acquires a bad implication that is missing when Czernobog says the same thing to a racially-undefined Shadow in the book.

I generally liked "American Gods" as a book though it did rehash a lot of Neil Gaiman tropes, like the former-fertility-goddess-now-forced-to-be-a-sex-worker plot line, that he already covered in his "Sandman" series. I adore the "American Gods" novelization for its extraordinary illustrations and multiple dimensions it brings to Neil Gaiman's book. If I have any complaints it is mostly about how women are portrayed. Most of the old goddesses in the book seem to be either sex maniacs (Bilquis, Bast (yes, the cat goddess)), or motherly figures who stand at the sidelines of the male-initiated plot lines, dipping in only occasionally when Shadow is in a tight spot. Even Lucy Ricardo from "I Love Lucy" shows her breasts! The reanimated corpse of Shadow's wife also seems mostly sex-defined (she died while giving a blow-job to Shadow's friend) who makes a half-hearted pass at Shadow. Shadow turns her down. "You're dead babe," he says in one of the best lines of the book.

Only one woman, a white feminist college student named Sam whom Shadow gives a ride to, appears to avoid being defined by sexual activity. Nevertheless Sam is mostly a ham-handed stereotype of middle-class white progressives, a privileged young woman who enjoys living the rough adventurous life a bit knowing that she has a soft place to fall. "I figure you're at school," Shadow says, "Where you are undoubtedly studying art history, women's studies, and probably your own bronzes. And you probably work in a coffee house to help cover the rent." He's exactly right in his assessment too. "How the fuck did you do that?" Sam asks, shocked.

Sam seems to see poverty as something to experience as an adventure tourist rather than an inescapable life trap. After picking her up hitchhiking on a cold country road Shadow drops Sam off at her aunt's wealthy suburban house. Sam is basically me in my twenties, I have to admit. And frankly Gaiman's parody of white feminist college students with his character of Sam touched a few nerves. Her scene with Shadow is easily the most badly-written part of "American Gods." Even the fantastic P. Craig Russell adaptations can't rescue the scene entirely.

My views on the portrayal of women in "American Gods" aside, the graphic novelization of Neil Gaiman's book is amazing. It has some of the best illustrations I have seen in years. The pictures evoke a wonderful sense of place, emotion, character and wonder that stretches almost beyond the parameters of the original book. A definite recommend!

In "American Gods" a man named Shadow, a guy who just served his time in prison for robbery, is offered a job by a "Mr. Wednesday" as a bodyguard. Shadow is at loose ends. He's an ex-criminal, his wife died while he was in prison and he has no job and nowhere to go. He is almost given no choice but to accept Mr. Wednesday's job. Mr. Wednesday turns out to be the personification of the Norse God Odin who, along with other pre-Christian Indo-European gods and various mystical figures masquerading as immigrants, is planning a war against various new gods such as the god of the internet and the god of television.

In the original novel "American Gods" Neil Gaiman is rather vague in describing Shadow physically. Shadow is a large, burly guy. "He was big enough and looked don't-fuck-with-me enough(.)" Gaiman implies in the book that Shadow is rather swarthy, leading a white prison guard at the beginning of the novel to ask him "And what are you? A spic? A gypsy? Maybe you got n***** blood in you. You got n***** blood in you, Shadow?" This exchange does not translate well in the graphic novel since Shadow is drawn as unambiguously black.

Shadow's blackness in the graphic novel of "American Gods" adds dimensions to the story that are missing in the book. The scene where Mr. Wednesday an old white man, intimidates Shadow into being his bodyguard takes on an uncomfortable sheen. The fact that Mr. Wednesday turns out to be a Scandinavian god, a figure in a pre-Christian culture that is fetishized by white supremacists, only makes the situation more uncomfortable. When Mad Sweeney, a leprechaun who takes on the form of a 7-foot white trucker with a baseball hat, punches Shadow in a bar it's hard not to see a MAGA-era hate crime. Mad Sweeney's baseball hat reads "The only woman I ever loved was another man's wife.... my mother." Still, it looks a lot like a MAGA hat. When another old white god, Czernobog, talks to Shadow about "your master" Mr. Wednesday the phrase suddenly acquires a bad implication that is missing when Czernobog says the same thing to a racially-undefined Shadow in the book.

I generally liked "American Gods" as a book though it did rehash a lot of Neil Gaiman tropes, like the former-fertility-goddess-now-forced-to-be-a-sex-worker plot line, that he already covered in his "Sandman" series. I adore the "American Gods" novelization for its extraordinary illustrations and multiple dimensions it brings to Neil Gaiman's book. If I have any complaints it is mostly about how women are portrayed. Most of the old goddesses in the book seem to be either sex maniacs (Bilquis, Bast (yes, the cat goddess)), or motherly figures who stand at the sidelines of the male-initiated plot lines, dipping in only occasionally when Shadow is in a tight spot. Even Lucy Ricardo from "I Love Lucy" shows her breasts! The reanimated corpse of Shadow's wife also seems mostly sex-defined (she died while giving a blow-job to Shadow's friend) who makes a half-hearted pass at Shadow. Shadow turns her down. "You're dead babe," he says in one of the best lines of the book.

Only one woman, a white feminist college student named Sam whom Shadow gives a ride to, appears to avoid being defined by sexual activity. Nevertheless Sam is mostly a ham-handed stereotype of middle-class white progressives, a privileged young woman who enjoys living the rough adventurous life a bit knowing that she has a soft place to fall. "I figure you're at school," Shadow says, "Where you are undoubtedly studying art history, women's studies, and probably your own bronzes. And you probably work in a coffee house to help cover the rent." He's exactly right in his assessment too. "How the fuck did you do that?" Sam asks, shocked.

Sam seems to see poverty as something to experience as an adventure tourist rather than an inescapable life trap. After picking her up hitchhiking on a cold country road Shadow drops Sam off at her aunt's wealthy suburban house. Sam is basically me in my twenties, I have to admit. And frankly Gaiman's parody of white feminist college students with his character of Sam touched a few nerves. Her scene with Shadow is easily the most badly-written part of "American Gods." Even the fantastic P. Craig Russell adaptations can't rescue the scene entirely.

My views on the portrayal of women in "American Gods" aside, the graphic novelization of Neil Gaiman's book is amazing. It has some of the best illustrations I have seen in years. The pictures evoke a wonderful sense of place, emotion, character and wonder that stretches almost beyond the parameters of the original book. A definite recommend!

I just wanted to write a quick book review of "Anya's Ghost" by Vera Brosgol. "Anya's Ghost" is a young adult graphic novel and a pretty decent little ghost story. In "Anya's Ghost," a sulky and disagreeable teenage girl named Anya tumbles down an abandoned well and meets a shy, polite ghost named Emily. Emily died in the 1920s after her family was murdered. According to Emily, the murderer chased her out of the house, whereupon she tumbled down into the same abandoned well, broke her neck, and died of dehydration. Emily's spirit languishes in the well for 90 years because she is unable to leave her bones. When Anya gets rescued, Emily is transported out of the well too because Emily's finger bone accidentally gets tangled in Anya's belongings.

The plot is decent but not too memorable. There are some twists that regular readers of thrillers and ghost stories will probably see coming a mile away (though the twists were a little surprising to me). More impressive however is that "Anya's Ghost" is a graphic novel told with NO narration boxes! Now that is very hard to do. In most graphic novels narration boxes are provided to give the artist a break. One quick narration box like "Later Emily and I went to the mall" and a panel showing Anya and Emily in a mall saves a whole bunch of drawing. Without a narration box the artist has to show a series of panels of Anya getting off her bed, Anya picking up her purse and Emily's finger bone, Anya walking down the stairs with Emily drifting after her, Anya walking out the door, Anya walking down the street, Anya walking to the bus stop, Anya sitting at the bus stop, Anya getting on the bus, Anya paying the driver, Anya sitting in the bus as it heads towards the mall, Anya getting off the bus, Anya walking inside the mall, Anya walking in the mall as Emily drifts beside her looking curiously at the shop windows.... all this to convey to the reader that Anya and Emily go to the mall. This type of purely visual storytelling can last pages and is a helluva lot of work to do for a graphic novel artist.... work that can be eliminated by one narration box of "Later Emily and Anya went to the mall." The lure of the narration box is strong with every graphic novelist. It's a great way to cheat a bit. Vera Brosgol resists the call of the narration box however, relying on dialogue and character as well as her own art skills to advance the plot in "Anya's Ghost." She pulls it off too! With no narration boxes the reader is able to get a much fuller view of Anya's world and Anya's character. This type of visual narration also helps stretch out suspense. Without going into too many spoilers here I will say that there are some GREAT, almost Hitchcockian suspense scenes going on at the end of "Anya's Ghost" that are magnified by the lack of narration boxes. I was on the edge of my seat watching Anya try to save her family and fix a frightening situation.

Another part of "Anya's Ghost" that I loved is the character of Anya. At the beginning of the book Anya is not a very sympathetic character. Even by moody teenage girl standards Anya is pretty nasty. She's in a bad mood all the time. When she falls down the well and meets EMily, she is very dismissive of Emily's tragic story and existence. Emily is such a polite and sweet little soul and Anya is very harsh towards her. Anya spends about two days down in the well. Then, while she is asleep, Emily hears two boys talking by the well. Emily wakes up Anya telling Anya that somebody has come and she needs to yell for help. Anya immediately does so and is rescued. Yet, as Anya is finally pulled up from the well, Anya makes no move or gesture to help Emily leave the well, like take a bone with her so Emily can finally leave the darkness and see the outside world. As Anya sees Emily's saddened face as the only person Emily has spoken to in 90 years leaves her behind...... Anya does nothing. Emily literally saved Anya's life and Anya doesn't do anything in return. When it later turns out that Emily DID leave the well with Anya, it was clearly through an accident on Anya's part and not through any intentional action where Anya wanted to help Emily in some way.

There is a really solid character arc with Anya. Throughout the story you see Anya slowly realizing how disagreeable and ungrateful she is towards her family and friends and how she needs to improve. It's hard to write a good character arc. It's even harder to write a good character arc in a graphic novel with no narration boxes! I was wowed by Brosgol's writing and pacing abilities. Her drawings are very attractive if a bit stylized. The pictures lay out the story cleanly. The dialogue and pacing keep the plot tight and pretty compelling. The characters are very well fleshed-out (with a few exceptions such as a silly subplot involving a boy Anya likes and the boy's popular girlfriend) and the book overall is a very satisfying read. If you have an hour to yourself (the story goes fast, you can read it in 45 minutes) and a hot cup of coffee do give "Anya's Ghost" a read.

The plot is decent but not too memorable. There are some twists that regular readers of thrillers and ghost stories will probably see coming a mile away (though the twists were a little surprising to me). More impressive however is that "Anya's Ghost" is a graphic novel told with NO narration boxes! Now that is very hard to do. In most graphic novels narration boxes are provided to give the artist a break. One quick narration box like "Later Emily and I went to the mall" and a panel showing Anya and Emily in a mall saves a whole bunch of drawing. Without a narration box the artist has to show a series of panels of Anya getting off her bed, Anya picking up her purse and Emily's finger bone, Anya walking down the stairs with Emily drifting after her, Anya walking out the door, Anya walking down the street, Anya walking to the bus stop, Anya sitting at the bus stop, Anya getting on the bus, Anya paying the driver, Anya sitting in the bus as it heads towards the mall, Anya getting off the bus, Anya walking inside the mall, Anya walking in the mall as Emily drifts beside her looking curiously at the shop windows.... all this to convey to the reader that Anya and Emily go to the mall. This type of purely visual storytelling can last pages and is a helluva lot of work to do for a graphic novel artist.... work that can be eliminated by one narration box of "Later Emily and Anya went to the mall." The lure of the narration box is strong with every graphic novelist. It's a great way to cheat a bit. Vera Brosgol resists the call of the narration box however, relying on dialogue and character as well as her own art skills to advance the plot in "Anya's Ghost." She pulls it off too! With no narration boxes the reader is able to get a much fuller view of Anya's world and Anya's character. This type of visual narration also helps stretch out suspense. Without going into too many spoilers here I will say that there are some GREAT, almost Hitchcockian suspense scenes going on at the end of "Anya's Ghost" that are magnified by the lack of narration boxes. I was on the edge of my seat watching Anya try to save her family and fix a frightening situation.

Another part of "Anya's Ghost" that I loved is the character of Anya. At the beginning of the book Anya is not a very sympathetic character. Even by moody teenage girl standards Anya is pretty nasty. She's in a bad mood all the time. When she falls down the well and meets EMily, she is very dismissive of Emily's tragic story and existence. Emily is such a polite and sweet little soul and Anya is very harsh towards her. Anya spends about two days down in the well. Then, while she is asleep, Emily hears two boys talking by the well. Emily wakes up Anya telling Anya that somebody has come and she needs to yell for help. Anya immediately does so and is rescued. Yet, as Anya is finally pulled up from the well, Anya makes no move or gesture to help Emily leave the well, like take a bone with her so Emily can finally leave the darkness and see the outside world. As Anya sees Emily's saddened face as the only person Emily has spoken to in 90 years leaves her behind...... Anya does nothing. Emily literally saved Anya's life and Anya doesn't do anything in return. When it later turns out that Emily DID leave the well with Anya, it was clearly through an accident on Anya's part and not through any intentional action where Anya wanted to help Emily in some way.

There is a really solid character arc with Anya. Throughout the story you see Anya slowly realizing how disagreeable and ungrateful she is towards her family and friends and how she needs to improve. It's hard to write a good character arc. It's even harder to write a good character arc in a graphic novel with no narration boxes! I was wowed by Brosgol's writing and pacing abilities. Her drawings are very attractive if a bit stylized. The pictures lay out the story cleanly. The dialogue and pacing keep the plot tight and pretty compelling. The characters are very well fleshed-out (with a few exceptions such as a silly subplot involving a boy Anya likes and the boy's popular girlfriend) and the book overall is a very satisfying read. If you have an hour to yourself (the story goes fast, you can read it in 45 minutes) and a hot cup of coffee do give "Anya's Ghost" a read.

Nice that Michael Wolff puts his libel lawyer at the top of his acknowledgements page. All in all, "Fire and Fury" is more about Bannon, whom Wolff seems to have spoken to most often, than Trump. Most of the juicy stuff has already been leaked. Less juicy revelations are pretty much self-evident (Bannon suffers from chronic heart failure and edema) or less self-evident but meaningless (Jared and Ivanka hate Kellyanne Conway and helped push her out of all meaningful White House roles). The most amazing stuff sounds like a Bannon-fed lie than what actually happened. (Jared and Ivanka, not Bannon, encouraged Comey's firing? C'mon. The "Let's tear down all the institutions" guy wanted Comey in place while the "Let's stay in the Paris Climate Accord and stay moderate" couple wanted Comey gone? Smh. Wolff should have been a little more dubious about that version of events.) If there is one over-arching theme to this book, it's that you cannot destroy and humiliate people without expecting them to fight back. People with a lack of empathy, like Trump and Bannon, spend their lives treating people with naked cruelty and then act surprised when their victims fight back. Why did Trump think Comey would just slink away after he got fired? Why did the White House think that Spicer, Preibus, Manafort, Bannon, Ailes, Flynn and all the rest wouldn't just go running to the nearest reporter or law enforcement officer after being tossed? Why was Trump surprised that after treating the Obamas like shit for years and women like shit for decades the streets would be flooded with anger and resistance instead of Trump-love after the inauguration? Trump shows why a lack of empathy is deadly for a politician. It not only makes him cruel, it makes him stupid. utterly adrift when his victims, instead of acting like victims, destroy him in the end.

It took me a long time to read this book because I really hated it. I loved Michael Chabon's "The Yiddish Policemen's Union" because it had a truly original premise. It was an alternate history where after WWII the Jewish state in Israel was established in a remote part of Alaska instead of the Middle East. Some problems in this history remain similar to our own (there are fights between Jewish settlers and Alaskan Inuit populations over land) and obvious differences (boy it's cold!). I love the book but the climax was unfortunately complicated and a little difficult to understand. "Summerland" has the same problems. It's too complicated in the way Chabon mashed up various mythologies and adventures and tries to make it all about baseball. He aims for a baseball-themed Neil Gaimon sort of story and instead gets a mess where any sort of forward momentum in the story gets held up by yet another game of baseball. Baseball is dull enough to watch but it's even more dull to read about. Even more annoying is that Chabon draws a lot on Native American mythology but the only Native American character, a truly interesting, touch, and competent young girl named Jennifer Rideout, has to step aside and let a very uninteresting and weak white boy named Ethan Feld save the day. it's the Hermione problem. "But Hermione is the better wizard! Why is it always Harry Potter saving the day?" Plus here again the climax is too complicated for me to understand, but the world is saved in a way that is supposed to be both mythic and cute. I guess. I didn't understand it. Ugh. Go read "Anansi Boys" instead.

I finished "We Were Eight Years in Power" by Ta-Nehisi Coates. It is not an easy book to read an not just because of the harsh subject matter. Coates has a stiff style of writing despite a few poetic turns of phrase (Coates calls America's jails "The Grey Wastes" and white supremacy "The Bloody Heirloom"). Nevertheless the book was not written for a reader's pleasure. It was written to show that America was founded on white supremacy and that has never changed, not even with the election of Barack Obama in 2008. Coates shows that America tends to rely on black politicians to fix the country after it lies in tatters. This happened after the Civil War. Black congressmen were elected during Reconstruction after the South lay in ruin. After the South got rich enough to get racist again Congressman Thomas Miller sensed the dangerous shift in tides as the South shifted away from Reconstruction and towards the KKK and the Jim Crow laws He pleaded to the South Carolina constitutional convention: "We were eight years in power. We had built schoolhouses, established charitable institutions, built and maintained the penitentiary system, provided for the education of the deaf and dumb, rebuilt the ferries. In short, we had reconstructed the State and placed upon the road to prosperity."

Unfortunately Miller's speech fell on deaf ears. And the South turned once again to deepest racism after having benefited from black leadership during Reconstruction. Coates draw a devestating parallel between the "eight years in power" in Miller's speech where black congressmen were called upon to fix a country in ruins and Obama's election in 2008 where he was called upon to fix a country in ruins after the Great Recession and Iraq War. The backlash against Obama with the Trump presidency should have been as predictable as the backlash against Reconstruction in the 1890s. "We Were Eight Years in Power" is basically eight essays written during each year in Obama's presidency by Coates for the "Atlantic." Some are pretty mediocre like "American Girl" about Michelle Obama. Even Coates acknowledged the essay has not "aged well," but it really suffered from the fact that Coates was not able to interview Michelle Obama before he wrote the article. Insight is painfully absent.

Better is Coates' main tentpole essay about Reparations. While reparations for slavery is obviously impractical (though Coates argues that it still needs to be studied, praising Congressman Conyer's bill asking for funding for the issue of Reparations to be studied. Unfortunately "We Were Eight Years in Power" was published a month before Congressman Conyers was forced to resign for sexual harassment). Nevertheless the black communities and black homeowners who were devastated by the Federal Housing Authority's "redlining" of districts that purposefully denied mortgages to black homeowners are still very much alive. Unlike those who suffered from slavery, those who suffered from mortgage discrimination and their children are around today. The denial of mortgages to black homeowners torpedoed any chance for a black middle class to flourish alongside a white middle class during the sixties, seventies, eighties and up to the present day. Those abused by the FHA deserved reparations according to Coates and it's hard to disagree with his reasoning.

Most beautiful and heartbreaking of Coates' essays is his last one where he recounts several conversations he had with President Obama during 2016. Obama had been steadfast in his belief during that time that Trump simply couldn't win. It was impossible. Coates was more skeptical. Coates makes an interesting observation about Obama's upbringing and Obama's faith in the white electorate to make the right choice. Unlike the vast majority of the black experience in America when it comes to interacting with white people, Obama's experience with white America was kindness and love. His case was exceptional in every sense of the word. Obama's mother and grandmother and grandfather never gave him any sense that he was not a family member during his childhood. Obama's white family members, according to his autobiography, never once gave the impression that black Americans were lesser than white Americans. This is so at odds with the experience of the majority of black Americans that it gave Obama, perhaps, a dangerously naive attitude when it came to placing his trust in the ultimate goodness of white people. "America will make the right choice, don't worry." Coates remembers how he became suddenly nervous when he heard Obama say that. Really?

Unfortunately Miller's speech fell on deaf ears. And the South turned once again to deepest racism after having benefited from black leadership during Reconstruction. Coates draw a devestating parallel between the "eight years in power" in Miller's speech where black congressmen were called upon to fix a country in ruins and Obama's election in 2008 where he was called upon to fix a country in ruins after the Great Recession and Iraq War. The backlash against Obama with the Trump presidency should have been as predictable as the backlash against Reconstruction in the 1890s. "We Were Eight Years in Power" is basically eight essays written during each year in Obama's presidency by Coates for the "Atlantic." Some are pretty mediocre like "American Girl" about Michelle Obama. Even Coates acknowledged the essay has not "aged well," but it really suffered from the fact that Coates was not able to interview Michelle Obama before he wrote the article. Insight is painfully absent.

Better is Coates' main tentpole essay about Reparations. While reparations for slavery is obviously impractical (though Coates argues that it still needs to be studied, praising Congressman Conyer's bill asking for funding for the issue of Reparations to be studied. Unfortunately "We Were Eight Years in Power" was published a month before Congressman Conyers was forced to resign for sexual harassment). Nevertheless the black communities and black homeowners who were devastated by the Federal Housing Authority's "redlining" of districts that purposefully denied mortgages to black homeowners are still very much alive. Unlike those who suffered from slavery, those who suffered from mortgage discrimination and their children are around today. The denial of mortgages to black homeowners torpedoed any chance for a black middle class to flourish alongside a white middle class during the sixties, seventies, eighties and up to the present day. Those abused by the FHA deserved reparations according to Coates and it's hard to disagree with his reasoning.

Most beautiful and heartbreaking of Coates' essays is his last one where he recounts several conversations he had with President Obama during 2016. Obama had been steadfast in his belief during that time that Trump simply couldn't win. It was impossible. Coates was more skeptical. Coates makes an interesting observation about Obama's upbringing and Obama's faith in the white electorate to make the right choice. Unlike the vast majority of the black experience in America when it comes to interacting with white people, Obama's experience with white America was kindness and love. His case was exceptional in every sense of the word. Obama's mother and grandmother and grandfather never gave him any sense that he was not a family member during his childhood. Obama's white family members, according to his autobiography, never once gave the impression that black Americans were lesser than white Americans. This is so at odds with the experience of the majority of black Americans that it gave Obama, perhaps, a dangerously naive attitude when it came to placing his trust in the ultimate goodness of white people. "America will make the right choice, don't worry." Coates remembers how he became suddenly nervous when he heard Obama say that. Really?

I just finished Derf Backderf's excellent graphic novel "My Friend Dahmer." "My Friend Dahmer" is a memoir about Backderf's teenage years in Ohio during the late seventies. During this time Backderf was apparently good friends with classmate and future serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer. Backderf's memoir is compellingly drawn. Backderf, like his contemporary Allison Bachdel, has a real gift for illustrating the everyday details of suburbia in Jimmy Carter's America.

Backderf inserts actual photos of himself and Dahmer at Revere High School in between chapters. One especially chilling group photo shows the clean cut, smiling high school students of the National Honor Society posed in an orderly, tiered crowd. One student in the photo has his face blacked out. This student was Dahmer, a failing alcoholic "D" student, who photo-bombed the National Honor Society group picture. Dahmer had snuck into the photo on a dare from his friends. A teacher, furious that Dahmer was in the photo but unable to retake the picture, blacked out Dahmer's face with a marker. The result, which was printed in the '78 Revere High School yearbook, is truly creepy.

Backderf's recollections of Dahmer show a great deal of red flags.... though to be fair it is impossible not to see red flags since no reader comes into the memoir innocent of Jeffrey Dahmer's reputation. Backderf blames the teachers of Revere for not intervening in Dahmer's slow slide into alcoholism, truancy, sadism and eventually murder. Dahmer's first murder occurred shortly after Dahmer and Backderf graduated from high school. Backderf is also straightforward in how he and his friends would also occasionally torment Dahmer. The relationship between Backderf and Dahmer was never a friendship of equals. Backderf would patronize, tease and manipulate Dahmer frequently. The picked-upon Dahmer would put up with Backderf's ersatz companionship just to have any relationship in high school that resembled friendship.

In the end, however, there is really no one to blame for Jeffrey Dahmer's murderous fate except Dahmer. Though Backderf tries to lay blame on Dahmer's parents' messy divorce and the Revere High School teachers' lack of involvement in their students' lives for Dahmer slipping through the cracks... Backderf's explanation rings a little weak. There is only so much the teachers could have been expected to notice. Dahmer was very manipulative and oddly charismatic in his own weird way. In one amazing scene Backderf describes Dahmer managing to sweet-talk his way into a meeting with Vice President Walter Mondale during a class field trip to DC. Dahmer was very adept at hiding his alcoholism, necrophilia and mental illness from the people in his life. Whether it be smoothly manipulating Walter Mondale or distracting several traffic cops from the suspicious garbage bags in the trunk of his car, Jeffrey Dahmer was that most dangerous breed of psychopath: insane enough to murder and stable enough to meticulously hide his deranged crimes from even those obsessed enough with him to remember every detail of his life forty years later.

Backderf inserts actual photos of himself and Dahmer at Revere High School in between chapters. One especially chilling group photo shows the clean cut, smiling high school students of the National Honor Society posed in an orderly, tiered crowd. One student in the photo has his face blacked out. This student was Dahmer, a failing alcoholic "D" student, who photo-bombed the National Honor Society group picture. Dahmer had snuck into the photo on a dare from his friends. A teacher, furious that Dahmer was in the photo but unable to retake the picture, blacked out Dahmer's face with a marker. The result, which was printed in the '78 Revere High School yearbook, is truly creepy.

Backderf's recollections of Dahmer show a great deal of red flags.... though to be fair it is impossible not to see red flags since no reader comes into the memoir innocent of Jeffrey Dahmer's reputation. Backderf blames the teachers of Revere for not intervening in Dahmer's slow slide into alcoholism, truancy, sadism and eventually murder. Dahmer's first murder occurred shortly after Dahmer and Backderf graduated from high school. Backderf is also straightforward in how he and his friends would also occasionally torment Dahmer. The relationship between Backderf and Dahmer was never a friendship of equals. Backderf would patronize, tease and manipulate Dahmer frequently. The picked-upon Dahmer would put up with Backderf's ersatz companionship just to have any relationship in high school that resembled friendship.

In the end, however, there is really no one to blame for Jeffrey Dahmer's murderous fate except Dahmer. Though Backderf tries to lay blame on Dahmer's parents' messy divorce and the Revere High School teachers' lack of involvement in their students' lives for Dahmer slipping through the cracks... Backderf's explanation rings a little weak. There is only so much the teachers could have been expected to notice. Dahmer was very manipulative and oddly charismatic in his own weird way. In one amazing scene Backderf describes Dahmer managing to sweet-talk his way into a meeting with Vice President Walter Mondale during a class field trip to DC. Dahmer was very adept at hiding his alcoholism, necrophilia and mental illness from the people in his life. Whether it be smoothly manipulating Walter Mondale or distracting several traffic cops from the suspicious garbage bags in the trunk of his car, Jeffrey Dahmer was that most dangerous breed of psychopath: insane enough to murder and stable enough to meticulously hide his deranged crimes from even those obsessed enough with him to remember every detail of his life forty years later.

It's odd when a book detailing a medical breakthrough that has saved countless lives reads like a tragedy. But that's how Rebecca Skloot's "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" comes off..... probably intentionally. In Skloot's excellent, gripping and exhaustively- researched book the story of Henrietta Lacks and her cells that miraculously survive and divide (in every sense of the word) to this day is laid out in full. Henrietta Lacks, a young wife and mother, came to Johns Hopkins Medical Center in 1951 because she felt a "knot" in her lower pelvis. She had cervical cancer, for which she was treated. Also (and herein lies the controversy), cancer cells were scraped from her cervix without Lacks' knowledge nor permission and sent to a medical research lab. The cells' incredible rate of growth led to many countless medical breakthroughs in cancer, blood pressure and heart conditions. Scientists previously could not test medications on human cells because cell lines tended to die off after a few cycles of reproduction. Not the HeLa line, as Lacks' cells were called. And thus medicine advanced by massive bounds in a relatively short span of time.

The history of Henrietta Lacks and the wounds felt by her family even now in the present day is hard to read but gripping. Would Lacks have been treated differently by the doctors at Johns Hopkins if she had not been a poor black woman? Her family says yes. Johns Hopkins says no. Skloot takes a more nuanced approach, acutely aware of her whiteness as she attempts to tell a black woman's story without being accused of appropriation. It's a very delicate line.

Skloot uses an interesting device where the medical boom in America that the HeLa cell line produced is told interspersed with chapters about Henrietta Lacks' family and the family's sad downfall after the death of Henrietta. The story of the Lacks family transcends medicine and even race. It is a story about the utter destruction that children experience when they suddenly lose their mother.